- 7 March 2016

- POST: General, Life & Politics

The sentence needs to be delivered with one hand firmly on your belly, with the elbow provocatively jutted out, as if it could be used to deliver a blow to the chest of your opponent. The other hand needs to be raised to face level, with palms looking up. With this pose of defiance, rightful indignation and potent anger, you deliver the phrase: “Sana ne?” It is only three syllables, but it is a key expression for Turks, halfway between “none of your business” and “what the hell do you care?” It combines stubbornness and total lack of desire to negotiate what is rightly one’s own decision.

“Sana ne” is generally a feminine expression. A 1975 song by Turkey’s self-declared superstar Ajda Pekkan, “What Is It To You Or Anyone Else?” coos about a woman’s claim that she was born free, will live her life the way she wants, and does not have to give account to anyone. The words are written by Ülkü Aker, a lyricist who has inflicted surprisingly feminist catch-phrases to pop songs of 1970s.

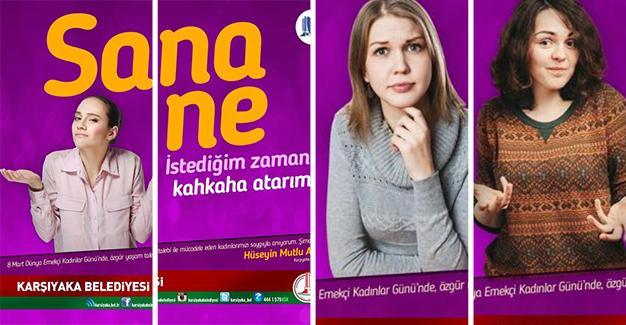

Forty years later, the “sana ne spirit” was revived in a set of March 8 posters by the Karşıyaka district in the western province of İzmir. The three posters, whose reception by the public has been controversial to say the least, directly aim to criticize the efforts to “blame the victim” when it comes to harassment cases against women.

“I will not bake pastry … and I will dress as I please. It’s none of your business,” says one poster.

“I will laugh as much as I want. It’s none of your business,” says another.

“I go out to have fun at night. It’s none of your business,” says a third.

The “you” may well be the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government and its loyalists. Most of the issues featured in the posters were raised, directly or indirectly, by AKP folks. “The fabric of the family is harmed if women do not know how to make a börek [Turkish pastry]” said Ayşen Gürcan, a former minister for Family and Social Affairs, last summer. “Decent women don’t laugh,” became one of the famous quotes by Bülent Arınç, an ex-deputy prime minister whose anti-feminist statements went beyond Turkey’s borders. “What was a young woman doing on the streets at two o’clock at night?” was tweeted by a pro-AKP journalist after a woman was raped in Istanbul, which created a counter-campaign, “What was a man doing in the streets with a knife at two o’clock at night?”

Karşıyaka’s “sana ne” campaign is a great way to express the anger of women about expressions that are patronizing at best and life-threatening at worst. The posters were plastered all over the city – an electoral bastion of Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu’s main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) – ahead of Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu’s two-day visit to the city, his first since the general election last November. In İzmir, Davutoğlu will meet hisGreek counterpart Alexis Tsipras, attend the Turco-Greek Business Council and convene the government at the brand-new Izmir Prime Ministerial Offices.

“This is a defiant, civilized part of the country where women’s response is not formulated in the language of the victim but with defiant humor,” said an entry in Ekşi Sözlük, Turkey’s online “devil’s dictionary” that immediately opened a page for Karşıyaka campaign.

But for others, only a small fraction of women enjoy the luxury of “sana ne” defiance, even in İzmir and other big cities. “So you have announced that it is no one’s business if you wear a miniskirt and come back at midnight in Karşıyaka,” said a critical entry in Ekşi Sözlük. “Big deal. I dare you put up the same posters in Ümraniye in Istanbul. When will the CHP learn to go beyond preaching the converted?”

Still, there is something about İzmir’s girls, with their overt self-confidence and strong sense of entitlement, that makes the wording just right.

“İzmir’s women are rebels. They play better cards than men and they wear shorts on the street. If you bother them, they simply give you a good slap,” said columnist Yılmaz Özdil once, in describing the women of his hometown. The article continues to be posted on social media four years after he wrote it.

Karşıyaka Mayor Hüseyin Mutlu Akpınar launched the campaign with the slogan, “Women are not behind us, we are side by side.” He now has the distinct place of heading a campaign that has caught the eye of the President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. “Some campaigns, under the pretense of advocating the liberty of women, are alienating them from the natural qualities that make women beautiful,” said the president.

For me, a non-native resident, İzmir’s women – with their soft tones of voice, lips darkened by the “Russian Red” lipstick, and hair lightened by the latest organic dye – are good at drawing their battle lines. The city’s non-governmental organizations, from the Journalists Association to the business groups, are either chaired or co-chaired by women. The women of the city are jokingly called “Topuklu Efeler,” or “warriors with heels.” The political participation of women who get elected from İzmir is high in all parties. CHP heavyweighs such as Selin Sayek Böke and Zeynep Altıok have their electoral base in İzmir. So does AKP Deputy Chair Nükhet Hotar. The architype of the İzmir girl is indeed a tough cookie. What other city’s woman has shouted an obscenity at the president from her balcony?

But it would be wrong to suggest that İzmir locals need no awareness against harassment. On the contrary, according to a survey carried out by the Health Ministry two years ago, the city tops the list of reported cases of violence against women (1,213 cases out of a total of 12,946). However, this probably means that the city, unlike others, actually has mechanisms through which women can report violence. “Unlike other cities, we have developed both legal and police mechanisms to allow women to report instances of harassment and violence,” said Nuriye Kadan of the İzmir Bar Association in a previous interview with the Hürriyet Daily News.