LOVE WEIGHS IN AT OZAN UNAL’S EXHIBITION

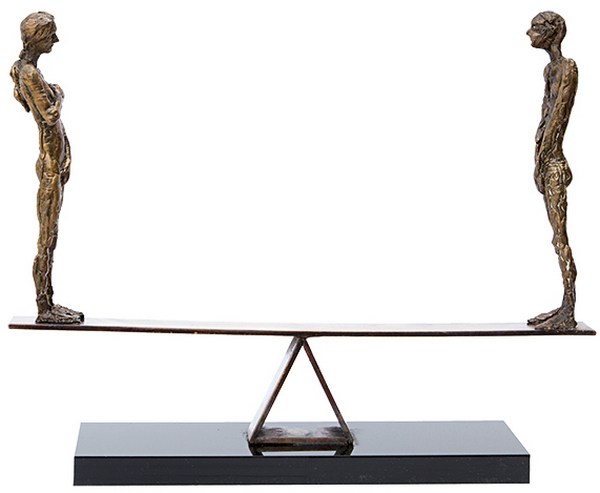

Artist Ozan Ünal’s latest exhibition ‘The Seesaw and the Spoilsport’ describes stages of courtship through statuettes of a man and a woman on a seesaw

Who wields more power in love? Is it the young and innocent, oblivious to their fragility? Or is it the one who is willing to give up first? Or is it the one who is keeping the balance through the right move at the right time?

Artist Ozan Ünal’s 15 bronze statuettes that consist of a man, woman and seesaw portray the different stages and possibilities of courtship: In one, a fragile young girl, with butterflies (symbols of fragile beauty and the short life of innocence?) tilts the seesaw in her favor, while, on the opposite end, the strong-looking man is drawn to her side, her head tilted sheepishly, as if he does not understand why he is not the one with more weight. The work is called “Charisma.”

Another work, titled “No Use,” shows a woman sitting on the end of the seesaw, her back stiff and defensive with rejection, while the male figurine is trying desperately to hold on to the seesaw to keep the balance. Iron figures climb toward each other with effort in “Bad Experience” or slide to the center as the seesaw changes shape in “Falling in Love.”

In “Platonic,” a lone woman’s figure stretches dreamily and voluptuously on the seesaw, leaving us wondering whether she is the object of desire for the masses or the subject of a long-ended love affair, still dreaming of a man gone.

“The Seesaw and the Spoilsport,” at Ekol Art Gallery in Karşıyaka, İzmir, reflects Ünal’s mastery of metal, as well as the marriage between images and words. The 42-year-old artist is a strong believer in the story behind each artwork, which he says is “just as important, if not more, than shadows, perspective or any other technical element.”

The second part of the exhibition, the “Spoilsport,” has a more politicized outlook. In the work called “Torture,” a male figure made of a mulberry tree kneels forward, with iron stitches representing wounds all over his body, albeit with determination carved on his face. In a nearby statue, a defiant iron figure extends his arms, his backbone in an arc. The statue, not surprisingly, is called “My Inner Voice.”

Inspiration from poems

Another larger-than-life status, called “Homo Boot-Lickerus,” shows a figure tilted forward, with the spine and neck bent in submission. The relationship between the name and the statue is no coincidence or result of a spur-of-the-moment decision. “I do not simply start with a piece of iron without knowing where it will end,” said Ünal. “My work starts with a concept, a word and then I sketch what I want to create. Often, my inspiration comes from poems, songs or an idea that I have read. I try not to complicate an idea too much, so that everyone can grasp it. There are moments that I tell myself that I should stop there and leave the rest to the imagination of the spectator.”

The 42-year-old artist studied fashion and design at İzmir’s Dokuz Eylül University. During university, he won prizes at the Beymen Academia Design Contest and Leather Days Design Contest. He represented Turkey in the Young Designer Seminar at the SAGA International Design Center in Denmark.

His habit of tying words to statues came from one of the professors, Ahmet Erinanç, who called him one day. “Erinanç, himself a poet, told me he liked what I wrote on my paintings, but he urged me to read as well as write. And I did, from Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s magical realism to Haruki Murakami.”

He built the Atelier Pi – Arts and Design Atelier in Karşıyaka, but ever since he has chosen to focus on iron, he moved his office to an industrial complex.

“I like the atmosphere there, with the artisans,” he told the Hürriyet Daily News. “I have been very observant with people, I watched them and their body language. I wanted my work to communicate to them – remind them of something they are familiar with.”

Some of his work is on display in public. His “2 July” Monument in Karşıyaka pays homage to intellectuals who were killed when an angry fundamentalist mob set fire to Sivas’ Madımak Hotel during an Alevi cultural festival in 1993.

His plans are to exhibit more in Ankara and Istanbul, as well as abroad. “There are some great galleries in İzmir, such as Gallery No2, Kedi Art Gallery or the Ekol Gallery, which has worked a great deal for this exhibition, but the opportunities in Istanbul are greater,” he said. “I have chosen my medium as iron,” he said when asked whether he would go back to painting again. “My series of black and white paintings, called ‘Mankind is not merely a black stain,’ are very popular, but I no longer want to turn to the canvas, at least not now,” Ünal said.